Prevalence

Pressure ulcers/Injury (PrUs), also commonly known as bedsores and decubitus ulcers, affect nearly 23% of patients in long-term and rehabilitation facilities.1 Incidence rates may be higher in intensive care units, where patients are less mobile and have sever systemic illnesses. PrUs have a significant impact on patient mortality and quality of life.

Risk Factors

Patients with limited mobility are at great risk for PrUs. Comorbidities such as diabetes, cerebral vascular accident, and hypotension can impair microcirculation. Over 70% of PrUs occur in patients older than 65 years of age.2 PrUs occur more frequently in African Americans.3

Pathophysiology

PrUs are a result of soft tissue compression between a bony prominence and external surface caused by prolonged pressure, friction or shear.4 In addition, PrUs can develop due to changes in aging skin and lowered tolerance to hypoxia.5

Assessment

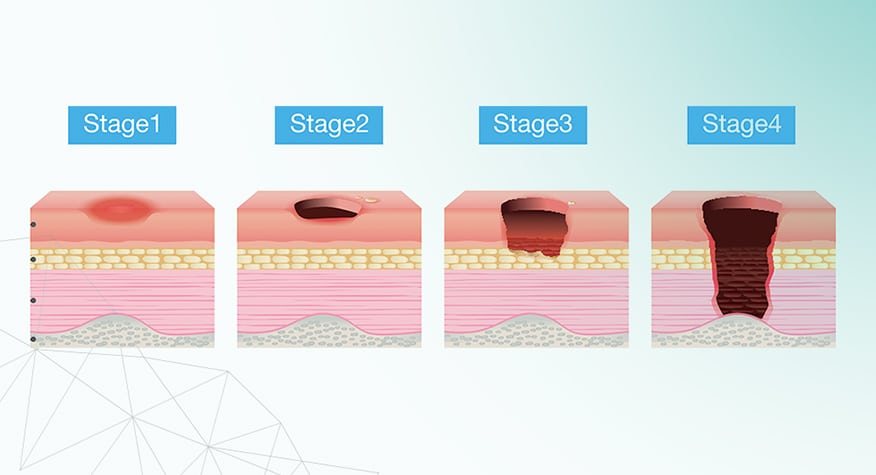

PrUs can range from mild non-blanchable erythema to severe tissue damage that extend to the muscle and bone. PrUs are classified according to severity:6

- Stage I- Intact skin with a localized area of non-blanchable erythema

- Stage II- Partial thickness loss with exposed dermis

- Stage III- Full thickness loss of skin, in which adipose (fat) is visible in the ulcer

- Stage IV- Full thickness skin and tissue loss with exposed or directly palpable fascia, muscle, tendon, ligament, cartilage or bone in the ulcer

- Unstageable- Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss in which extent of damage cannot be confirmed

- Deep Tissue Pressure Injury- Intact or non-intact skin with localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark wound bed or blood-filled blister

Prevention and Treatment

An assessment is essential to identify patients at risk as early as possible. Hospitalized patients at risk should be turned and repositioned as much as possible. Use of specialty mattresses and cushions may also lower the risk. Additionally, nutritional supplementation may be appropriate for patients who are malnourished. Negative wound pressure therapy (NWPT), offloading, debridement of devitalized tissue, and infection management are the mainstays for PrUs management.8

References

- Russo CA, Elixhauser A. Hospitalizations Related to Pressure Sores, 003: Statistical Brief #3. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD);2006.

- Whittington K, Patrick M, Roberts JL. A national study of pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence in acute care hospitals. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2000;27(4):209–215.

- Harms S, Bliss DZ, Garrard J, et al. Prevalence of pressure ulcers by race and ethnicity for older adults admitted to nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(3):20-26. doi:10.3928/00989134-20131028-04.

- Mervis JS, Phillips TJ. Pressure ulcers: Pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):881-890. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.069.

- Sree VD, Rausch MK, Tepole AB. Linking microvascular collapse to tissue hypoxia in a multiscale model of pressure ulcer initiation. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2019;18(6):1947-1964. doi:10.1007/s10237-019-01187-5.

- The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Pressure injury states. wnpiap.com.2016.

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016: 43(6), 585-597. doi:10.1097/won.0000000000000281.

- Boyko TV, Longaker MT, Yang GP. Review of the Current Management of Pressure Ulcers. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2018;7(2):57-67. doi:10.1089/wound.2016.0697.